News | September 18, 2004

NASA Orbiters Help Track Storms

By Kimm Groshong , Staff Writer

Article Published: Saturday, September 18, 2004

Pasadena Star News

LA CANADA FLINTRIDGE -- We now know that Hurricane Ivan's destructive eye first came ashore in the United States with its 130-mph winds Thursday near Mobile, Ala. But last weekend, forecasters were predicting a different course one that would have led the storm to strike Florida first.

Such uncertainty can contribute to public distrust of disaster warnings and insufficient preparation for storms. But hurricane prediction is a tremendously complex process that requires the consideration of dozens of factors.

To improve hurricane tracking and prediction methods, researchers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory are collecting and analyzing data related to those factors gathered by several lab-managed NASA instruments flying aboard Earth-orbiting satellites.

"The whole system is enormously complex,' said Eric Fetzer, the validation scientist on JPL's Atmospheric Infrared Sounder suite on NASA's Aqua satellite. "The more detailed information we have of the system as a whole, the better we can predict storms.'

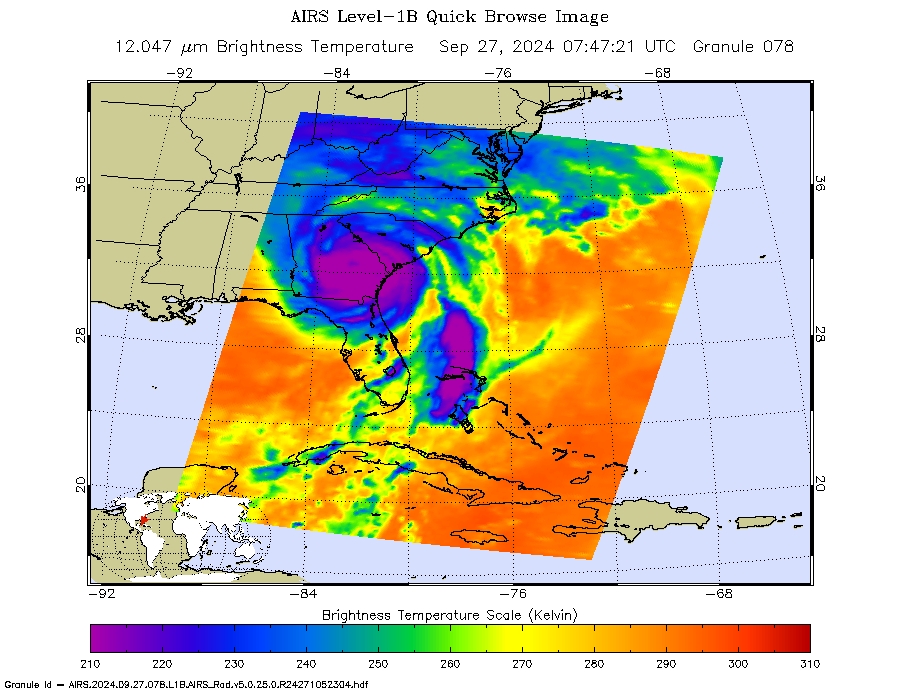

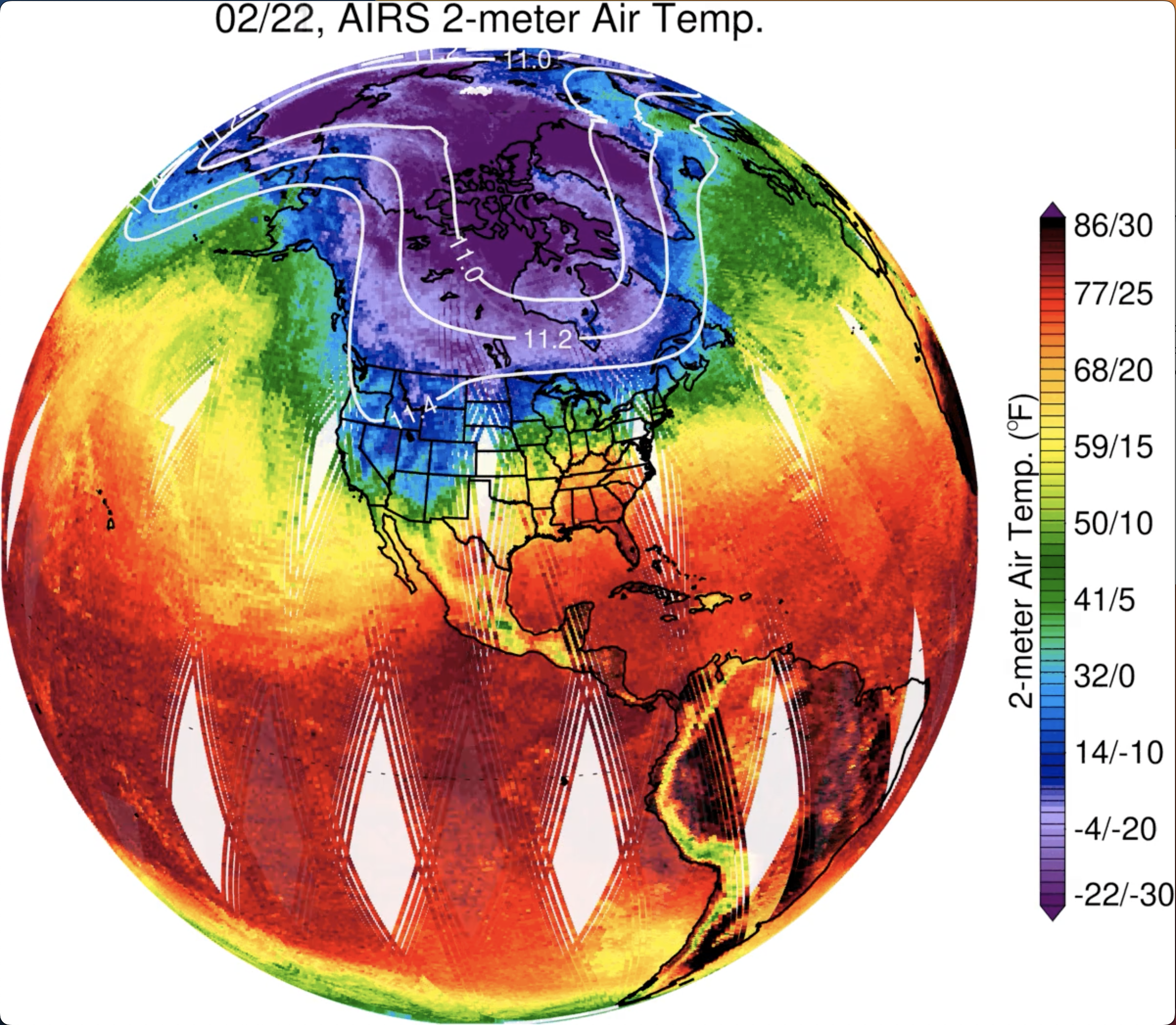

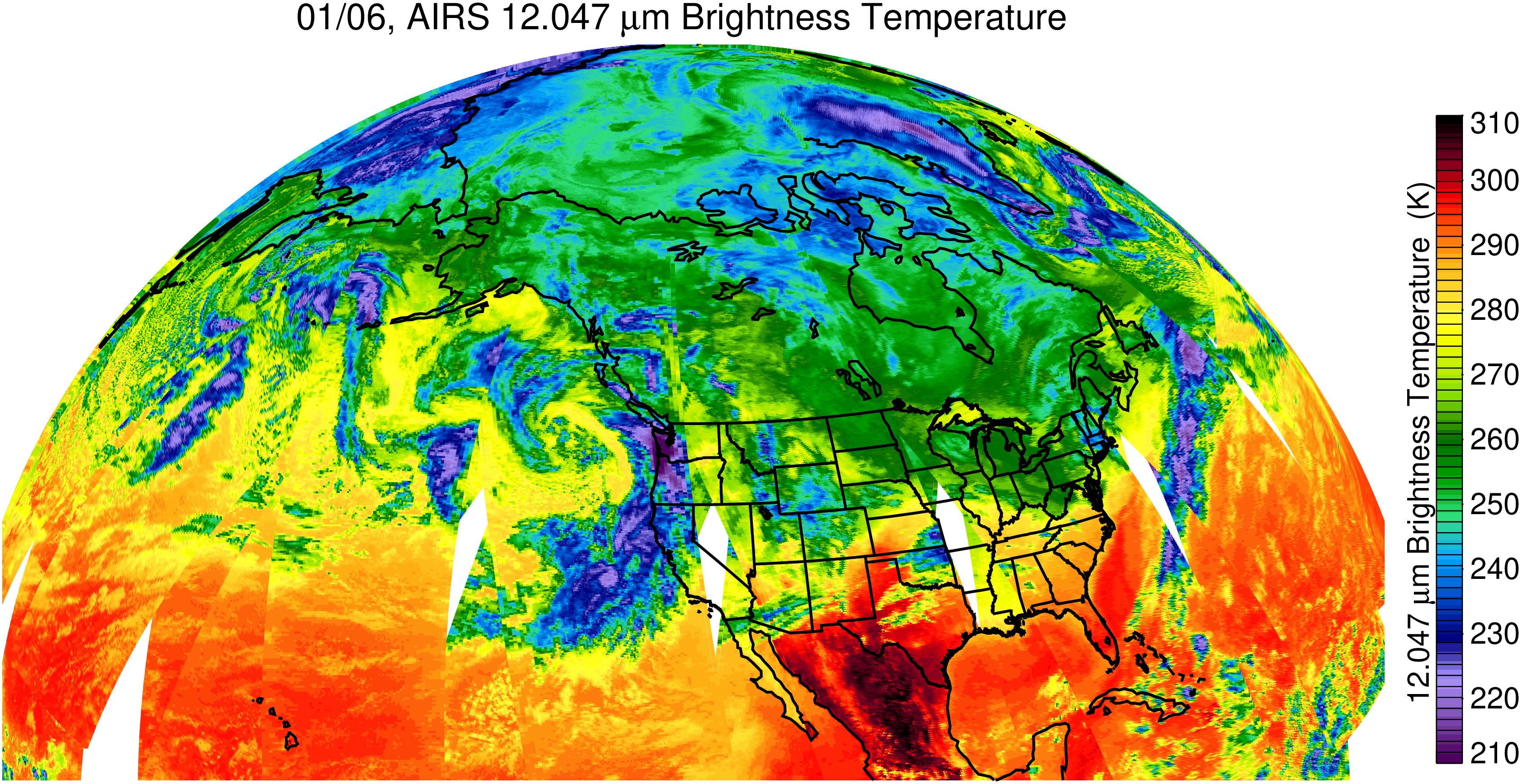

AIRS contributes detailed global humidity and temperature measurements of the lower atmosphere. The experiment can pierce up to 70 percent cloud cover using its microwave sounder and can use its infrared sounder for night vision. The resulting data could lead to better weather forecasts, which scientists say would improve hurricane prediction.

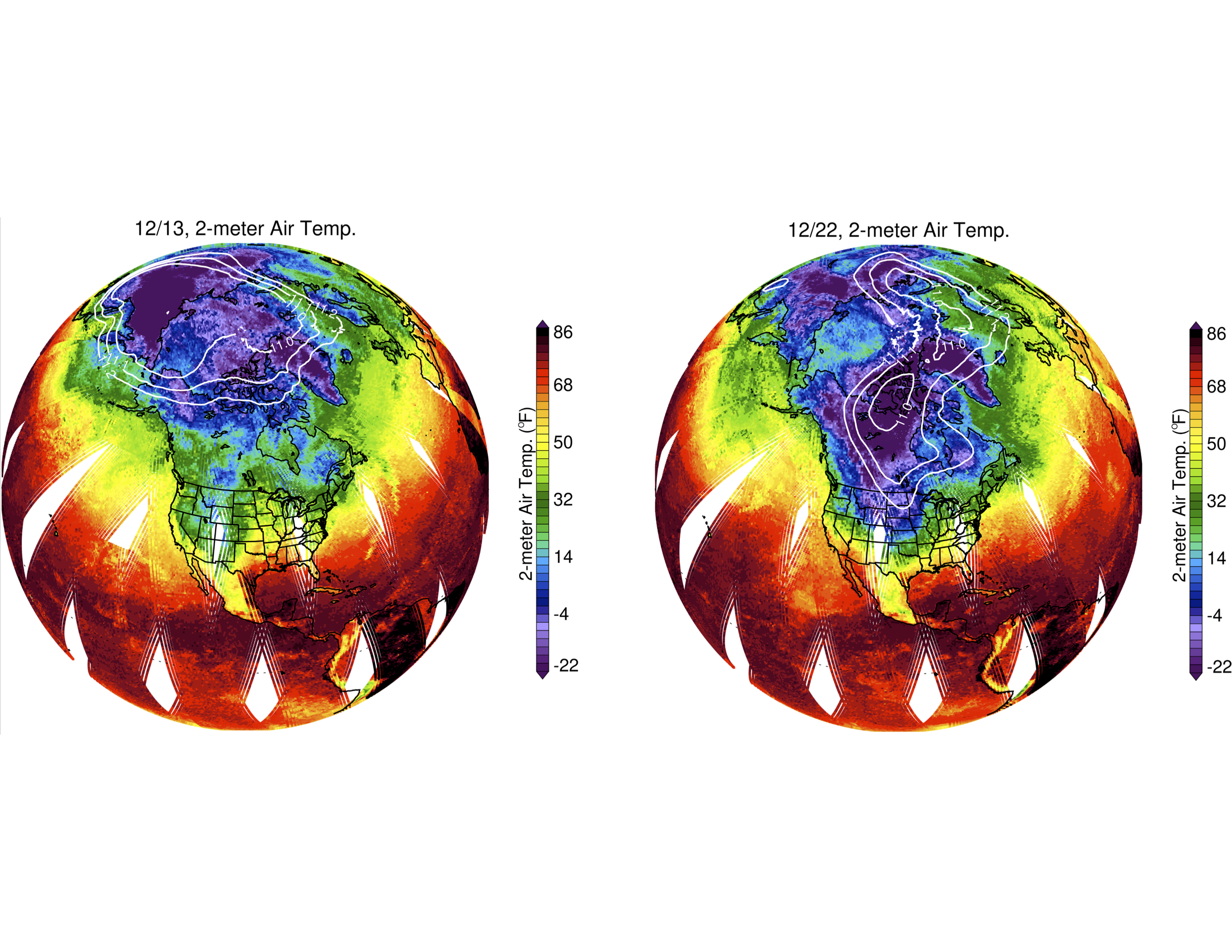

The lead scientist at JPL for AIRS, Bjorn Lambrigtsen, said forecasters originally predicted Ivan would first hit Florida because two high pressure systems that appeared stable would have funneled the storm right between them to the Panhandle. But those systems weakened and moved westward unexpectedly.

"The forecasts for the hurricane had to be changed because the forecast of the weather conditions did not hold,' Lambrigtsen said. AIRS researchers aim to improve surveillance and understanding of the atmosphere, he said, "so forecasters will be able to stick to their predictions.'

More data come from a JPL-managed device called an altimeter aboard the Jason-1 satellite. The device allows scientists to map the large-scale temperature patterns in the world's oceans.

"Jason-1 allows us to visualize large patterns of heat in the Pacific,' said William Patzert, a JPL oceanographer. He said ocean heat in the Pacific is closely related to the severity of the Atlantic hurricane season through a 25-year cycle called the Pacific Decadal Pattern, which he monitors in part using Jason-1.

The altimeter determines ocean water height by measuring the distance between the spacecraft and the water on Earth using radar technology. Ocean height correlates to ocean heat because water expands when it is heated. Those two factors, ocean height and temperature, are key determinants of hurricanes' size and intensity since the storms thrive on heat and moisture from the ocean.

Another major factor in hurricane prediction is wind. JPL's SeaWinds instruments on Japan's Midori 2 and NASA's QuikScat satellites can detect the direction and speed of circulating winds above the ocean that can lead to tropical cyclones earlier than other instruments. The National Atmospheric Administration's National Hurricane Center uses SeaWinds' data and the input from other NASA satellites to make early assessments of developing storms.

Today, much of hurricane prediction relies on computer models that use various parameters to simulate likely future events. The data from some JPL projects enhance those models' accuracy.

For example, JPL's Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer on NASA's Terra satellite snapped images of Hurricanes Frances and Ivan to help scientists evaluate the performance of their models.

MISR's nine high-resolution cameras compile maps of global cloud heights. Those maps provide scientists with information about the dynamics of upward moving air in hurricanes, said Greg McFarquhar, a member of the MISR team from the University of Illinois, Urbana- Champaign.

What happens at those higher levels in the atmosphere "does have an impact on the strength (of the hurricane), size of winds, strength of the storm surge, precipitation, flooding and winds,' he said.

Scientists such as McFarquhar run various versions of models and compare which results most closely resemble what happened in real life.

-- Kimm Groshong can be reached at (626) 578-6300, Ext. 4451, or by e-mail atkimm.groshong@sgvn.com .